I was asked “Who invented instant coffee” and I was ready with a typical (for me) clever, smart-alecky but informative response. But I like to fact check. And as I traveled down that particular internet rabbit hole, I found that my clever, smart-alecky response was not as informative as I thought. Here’s what I found.

Although a popular internet meme will tell you that George Washington invented instant coffee, A. It wasn’t THAT George Washington and B. He wasn’t the first. John Dring of England received a British patent for “coffee compound” in 1771, marking the first recorded occurrence of an instant coffee powder.

What is Instant Coffee?

Early Methods of Making Instant Coffee

John Dring

Coffee Essence

Mysterious French Discoveries

Mysterious American Discovery

Extract of Coffee and The Civil War

Alphonse Allais and Soluble Coffee

David Strang’s Patent Soluble Dry Coffee-powder

Satori Kato

Faust Coffee

G. Washington’s Prepared Coffee

Current Methods

Nescafé

Spray Dried Instant Coffee

Nescafe and World War II

Freeze Dried Instant Coffee

What is Instant Coffee?

Instant coffee is, in fact, made from brewed coffee. The manufacturing process involves removing the water from the brewed coffee using one of several methods. The resulting powder, crystals, or concentrated liquid can be rehydrated into a drinkable, brown, caffeinated beverage by simply adding hot water.

I know… I’m being a little snarky. Instant coffee is undoubtedly convenient. It just takes a spoonful in a cup of hot water. It is less messy to prepare because there are no spent grounds to deal with. When stored properly and kept dry it can have a long shelf life compared to roasted coffee beans. However, instant coffee often gets a bad rap for taste. Historically, this reputation has been deserved.

Early methods involved boiling brewed coffee until the water was entirely evaporated. As we know, the temperature of the water during brewing is crucial to maintaining a favorable flavor pallet. Remembering the old saying, “Coffee Boiled is Coffee Spoiled!” might give us a clue to the reason for the less-than-ideal taste. Current techniques do not involve boiling the coffee but there are still several steps in the process. Making instant coffee crystals and powders may involve brewing at excessively high temperatures, freezing, and evaporation. There is undoubtedly potential for flavor degradation. The use of inferior varieties of coffee, such as Robusta, and substandard beans compared to those used in specialty coffees probably also is a factor.

Early Methods of Making Instant Coffee

Further proof that there is nothing new under the sun, there is evidence of what we would recognize as “cold brew” as far back as 17th century Japan. Possibly introduced to them by Dutch traders (or maybe it was the Japanese who introduced the Dutch to the process they were using to brew tea) who wanted to brew large quantities of coffee for later enjoyment, this probably did not have a very long shelf life and would be unsuitable for long-term storage. I only mention it in the spirit of completion.

John Dring

In 1771 John Dring was awarded a British patent for “coffee compound.” Mostly lost to history, there are some hints that this was a dried, brewed coffee pressed into a cake. Reports are that it spoiled too quickly and so was not successful as a retail product. I found an earlier 1768 patent by Dring that was for a dried “just add water” writing ink product that was formed into a cake or tablet. He is also listed on a patent in 1771 for an “Apparatus for and mode of drying coffee.” These are definitely questions that deserve further research.

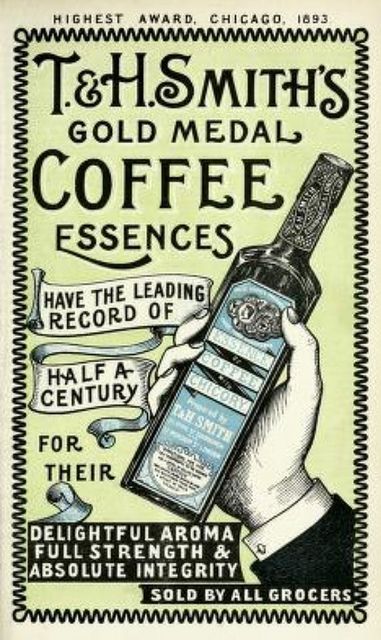

Coffee Essence

In 1840, the Scottish company T & H Smith developed the first concentrated “coffee essence.” This highly concentrated liquid was prepared by percolation and quick evaporation to about 1/3rd or 1/4th of its volume. It was then mixed with a thick extract of chicory and a syrup of burnt sugar. The consistency was similar to molasses and was said to taste like coffee-flavored light molasses. A standard serving was one or two teaspoons per cup of boiling water. It was sold in a bottle at pharmacies and grocery stores. Later that century, a similar product, Camp Coffee, was marketed out of Scotland.

Mysterious French Discoveries

According to William H. Ukers in his 1922 classic “All About Coffee,” there are two mysterious French patents that I have so far been unable to chase down. In 1852, someone named Tavernier was granted a French patent on a “coffee tablet” and in 1853 two people named Lacassagne and Latchoud were granted a French patent on “liquid and solid extracts of coffee.” My curiosity is piqued because both of these appear to be methods to produce some sort of an “instant” coffee. In fact, there are a number of “coffee tablet” patents on file in the US as well. They all involve the extraction of coffee, drying and evaporation, and compression of the resulting solids. Future research will surely tell the tale.

Mysterious American Discovery

I have seen multiple references to an American product invented in 1851 or 1853, depending on the source. However, these references seem to have been copied from the same source or, more likely, each other. I have found no further details as of this writing, although the authors of those articles seem to erroneously think that an invention in the early 1850s was made to supply the troops during the American Civil War (1861-65).

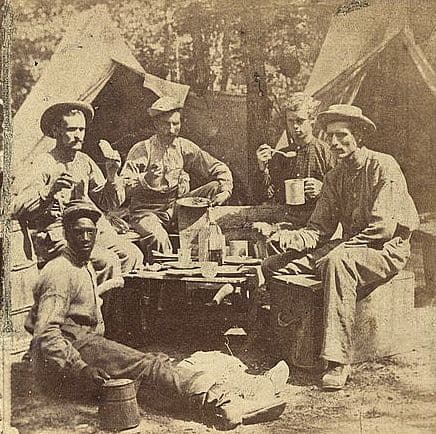

Extract of Coffee and The Civil War

Thanks to the tax on tea that in part sparked the Revolutionary War in America, coffee quickly gained popularity in the new nation. By the time of the American Civil War, some 85 years later, coffee was thoroughly entrenched in the American diet. In fact, it was included in standard army rations beginning in 1832. Supplying that much coffee to troops in battle must have been a logistical nightmare. A 20-day coffee and sugar ration for 100,000 men weighed in at 250 tons. And let’s not minimize the time that all that roasting, grinding, and brewing takes. Time is something that can be in short supply during battle.

Enter Extract of Coffee. In the mid-1850s the Borden company had developed a reliable method for condensing milk using a vacuum. It was short work for them to develop a concentrated coffee, milk, and sugar mixture for the Union army. This took up half the space and weight of the existing coffee rations and so freed up wagon space for more important war materiel. Eventually, similar products became available as “Essence of Coffee” under the manufacturer names of Bohler & Weikel, George Hummel, and others. It is often reported as being unpopular with the troops due to spoilage. It has been suggested that any bad reports might have been the result of it being mixed with bad milk or water. Modern Civil War reenactors who have replicated the recipe swear to its tastiness and shelf stability. My preliminary research indicates that the real reason was probably political nonsense and/or graft-related.

There is a ton more to discover on this subject, including various coffee substitutes used by the troops, port blockades, and even a “coffee powder” from The American Desiccating Company that never quite got off the ground. I suspect I will do a dedicated article on coffee in the Civil War in the near future. Sign up for the email and you will know when it hits.

Alphonse Allais and Soluble Coffee

Once upon a time, there was a French humorist named Alphonse Allais. He was a columnist who wrote funny and absurd stories for the Parisian newspaper Le Chat Noir (The Black Cat) and several others during La Belle Époque (1871 – 1914). One of his “bits” was to propose ridiculous inventions, for example: a fish tank made out of frosted glass for shy fish. Just silly.

It is also claimed that he invented some sort of instant coffee and was awarded a patent in 1881. Below is a very hard to decipher image of a French patent numbered #141,530 (not 141520 as is reported ad nauseum on various coffee lists) that is claimed to be authentic. I have not found independent verification of a patent of this number, nor any image of a French patent of this era to compare it to. Allais’ father was a pharmacist and Allais himself had some scientific training, so it is possible. However, after a search of spectacular proportions, I am not convinced that this wasn’t an elaborate practical joke. In spite of this, I may have become a fan of his work.

Strang’s Patent Soluble Dry Coffee Powder

Using a “Dry Hot-Air” method, David Strang was awarded an 1890 patent in New Zealand. A spice merchant by trade, this process likely utilized a spice dryer he had patented a few years before to blow very hot air across brewed coffee until the water was evaporated. According to the local newspaper of the time, he began selling tins of “Strang’s Coffee” in 1889.

Satori Kato

This Japanese inventor of soluble tea developed a method for separating the volatile oils from the coffee between 1899 and 1901. This allowed the oils to be recombined with the dried product, preserving flavor and extending its shelf life. He presented his product at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in 1901. Kato received a US patent for his process in 1903.

Faust Coffee

We can thank a spilled drop of coffee for this invention. Coffee and tea merchant Cyrus Blanke noticed that a spilled drop of coffee on a hot pie plate had evaporated, leaving behind a dry residue. Realizing that adding water to the powder turned it back into coffee, he quickly began production and brought it to market in 1906. He named it after the restaurant the incident occurred: Tony Faust’s Oyster Café in St. Louis.

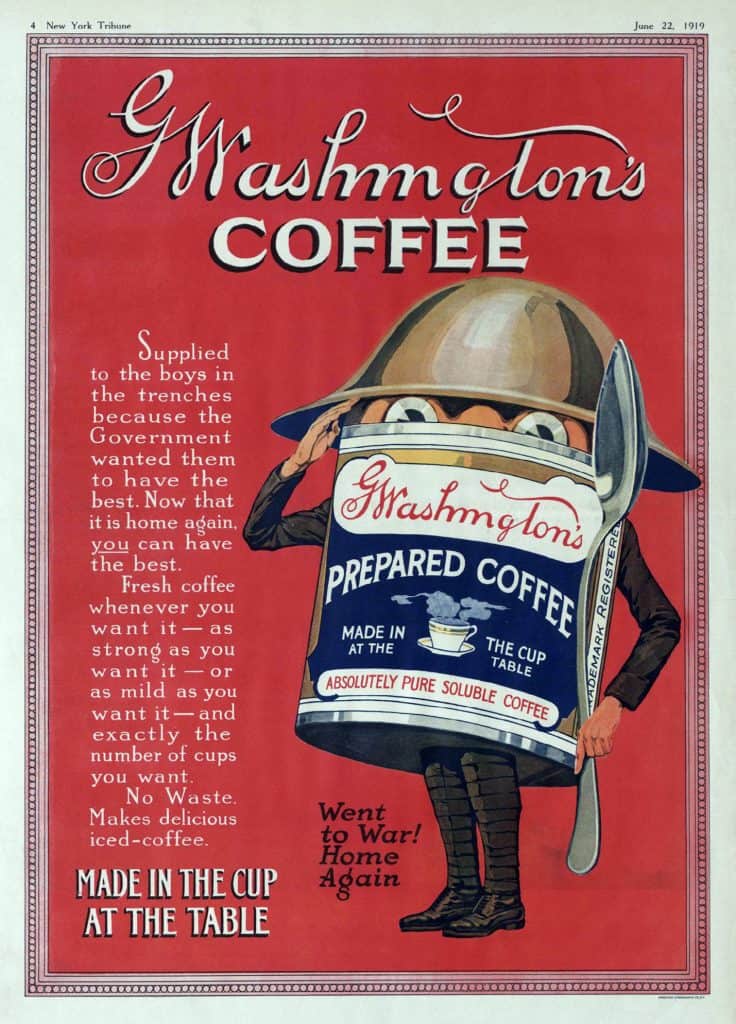

G. Washington’s Prepared Coffee

Around the same time as Blanke was selling Faust Coffee, George Constant Washington noticed some dried coffee on the spout of his coffee pot. As a seasoned inventor with over two dozen patents, his mind must have gone straight to work. Using a secret process that was never patented, by 1909, Red E Coffee was on the market. In 1910 it was re-christened G. Washington’s Prepared Coffee. Washington’s biggest advantage was the fact that, unlike those before him, he was able to mass produce his coffee. Online sources indicate that it was considered a novelty and was not particularly popular due to its lackluster taste. But George had another bit of good fortune. Timing.

As we discussed earlier in the Civil War section, coffee is part of a soldier’s daily food rations. Transporting whole bean coffee is a logistic nightmare. But a powder that can be individually dosed in envelopes? That’s doable. The G. Washington Coffee Refining Company was ideally suited to take on the task. And then World War I happened. At its peak, G. Washington was producing 40,000 pounds of coffee per day in ¾ ounce envelopes, 24 to a can. Despite its taste, soldiers in the trenches were happy to get their “cup of George.”

Current Methods of Instant Coffee Manufacturing

Modern instant coffees are primarily produced by either a Freeze-Drying process or a Spray Drying process. Here’s how we got from there to here.

Nescafé

In the wake of the stock market crash in 1929, the Banque Française et Italienne pour l’Amérique du Sud found itself with a large surplus of coffee beans in its warehouses. The chairman of Nestle, Louis Dapples, a former banker himself, was asked to help out. Nestle took on the task of creating a soluble coffee product. Hiring chemist Max Morgenthaler was key to helping the company’s researchers find a solution. Using a series of percolators to create a coffee concentrate, mixing it 1:1 with corn syrup, and then spray-drying it proved to be key. Nescafé was launched in 1938.

Spray Dried Instant Coffee

Spray drying is achieved by spraying liquid coffee concentrate as a fine mist into very hot, dry air (we’re talking about 480 degrees F). By the time the coffee hits the floor of the chamber the water has been evaporated and it has dried into small, round crystals. This is then further treated with steam so as to clump into a shape reminiscent of ground coffee.

Nescafé and World War II

Taking a page out of the G. Washington book, being a primary supplier to the US military did wonders for Nescafé. The bulk of their production was sent to the troops. They even set up two additional production facilities in the US. But the war was about to produce a second lucky coincidence to help produce better instant coffee.

Freeze Dried Instant Coffee

During the war, research into the long-term storage of organic materials led to the development of high vacuum technologies to produce penicillin and blood plasma. After the war, peacetime uses led to such advancements as concentrated orange juice.

Freeze drying coffee involves a few steps. First, the coffee flavors are extracted at a high temperature of 175°C (347°F). The best temperature for brewing coffee is in the 194-204ºF range. The coffee extract is then rapidly chilled into a slush and then further chilled to -40ºC (and F, too – It’s the same temperature in both!) to form slabs of coffee ice. The coffee ice is broken into small bits and subjected to a warming vacuum. This causes the ice to sublimate (go from solid to vapor while skipping liquid), leaving behind the instant coffee granules. If you are going to drink instant, freeze-dried is the way to go.

UBOI 85% of Russians prefer instant coffee to brewed

Conclusion

We coffee drinkers are in an exciting time. There is seemingly a café on every other corner, serving coffees grown in exotic locations from all over the world. Those of us who like our pour overs, arguing the subtleties of cold brews, and comparing our choices using the flavor wheel may not realize that much of the world likes their instant coffee. Whether as a first choice or a necessary evil when camping, almost 50% of world coffee production goes into making instant.

It’s also hard to imagine a time when coffee was so new that there were still discoveries to be made. Heck, even freeze-dried coffee has been available on the grocery shelves for most of my life. From the early Dutch traders concentrating their coffee so they could have a more convenient supply of the good stuff, to the tentative first steps of John Dring and his “coffee compound, through the sugary coffee essences and the rediscovery of evaporation techniques, to the modern freeze dried production of today, the science has marched on. Recent reviews of Starbucks Via Instant Coffee have been glowing. At $1 a cup, it isn’t cheap but it seems to be both quite tasty and quite convenient.

Who knows where the science will take us? Rest assured; the industry is still taking steps to improve the product. If you have any questions, feel free to leave them in the comments below. I read them all.

Be part of Procaffeination Nation!

If you like coffee and fun, join us in our Procaffeination Facebook Group. To be among the first to find out when the book is ready (and probably get a discount, too) sign up for the email list. No spam… I promise.